At a glance, Nigeria’s health system appears to be sustained not only by hospitals and clinics, but by an expansive informal healthcare economy operating in parallel. More than half of births in the country occur without a skilled birth attendant, and only about 10% of Nigerians are covered under the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA).

Nigeria operates roughly 40,000 health facilities, serving 200 million people. Eighty-eight percent of them are classified as Primary Health Care (PHC) centres. Yet only about 60% of the population has functional access to PHC services. The country has approximately 2.9 doctors per 10,000 people, far below WHO recommendations, and nearly 80% of doctors are concentrated in urban areas. Out-of-pocket spending remains the dominant financing model.

These gaps have predictable consequences: households increasingly rely on patent and proprietary medicine vendors (PPMVs), traditional birth attendants (TBAs), unlicensed drug shops, and faith healers. Their appeal is obvious: proximity, flexible payment, familiarity, and availability when formal facilities face stockouts, long wait times, or workforce shortages. This has, nonetheless, created systemic issues that require further examination.

Also Read: Future of Digital Health in Nigeria

What informal healthcare looks like

In rural and underserved communities, the first point of care for illness is often the local PPMV, many of whom lack formal pharmacy training. A 2021 study in rural southeastern Nigeria found that 75% of residents initially sought treatment from informal drug shops rather than clinics. For childhood illnesses, informal providers are often the first source of care, with estimates ranging from 8% to 55% depending on condition and location.

Maternal health illustrates this reality starkly. According to the 2024 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS), only 46% of births were delivered by a skilled birth attendant.

This does not necessarily reflect rejection of modern medicine; rather, it highlights gaps in affordability, access, trust, and facility readiness.

Beyond maternal and child health, traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine remains widely used. Government and WHO estimates suggest a majority of Nigerians use some form of traditional medicine, particularly for chronic or culturally embedded conditions. For many communities, herbalists, bone-setters, and faith-based healers remain first points of care.

Informal care is therefore no longer marginal but has become embedded in everyday health-seeking behaviour.

The cost of informal healthcare

While informal providers increase short-term access, they often shift costs into the future. Misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment are common in low-resource settings. Febrile illnesses are frequently treated presumptively as malaria.

Antibiotics are widely dispensed without proper indication, contributing to antimicrobial resistance (AMR). According to global estimates from Management Sciences for Health, AMR contributes to hundreds of thousands of deaths annually across sub-Saharan Africa, with Nigeria bearing a significant share. Nigeria accounts for roughly 29% of global maternal deaths, with an estimated 75,000 maternal deaths annually. Infant mortality remains high at over 100 deaths per 1,000 live births.

Informal care is not the sole cause of these outcomes, but delayed referrals, poor aseptic technique, and lack of emergency obstetric capacity significantly increase risk when complications arise.

Systemically, informal care leads to fragmented service delivery. Patients often move between chemists, herbalists, and clinics without coordinated records. Formal providers may also be unaware of medications already taken. Severe cases may arrive late at hospitals, when conditions have deteriorated.

There are also surveillance implications. Cases managed entirely within the informal sector are rarely captured in national reporting systems. This weakens outbreak detection, distorts planning data, and limits accountability. Weak regulation further creates space for substandard or counterfeit medicines, compounding risk in an already resource-constrained system. On one hand, informal care appears to expand access. But on the other hand, it leaves little room for accountability in a do-it-yourself system of healthcare.

The case for integration

Despite their reach, informal healthcare providers remain largely excluded from structured health policy frameworks. Reform efforts have focused on hospitals, insurance expansion, and strengthening formal facilities, while the informal care economy continues to operate in parallel.

Regulatory frameworks exist, but enforcement is uneven. Integration mechanisms — training, referral pathways, surveillance inclusion — remain weak.

Whether informal providers should exist remains secondary to the primary policy question of how they should be governed.

A better approach could be to prioritize structured integration: standardized training, defined referral pathways, supervisory linkages to PHCs, and inclusion in disease surveillance systems. Strengthening these linkages would reduce preventable harm while preserving the access and proximity that make informal providers attractive in the first place. Integration, for all its benefits, cannot, however, be a complete substitute for structural reform.

Tapping into the opportunity: A strategic path forward.

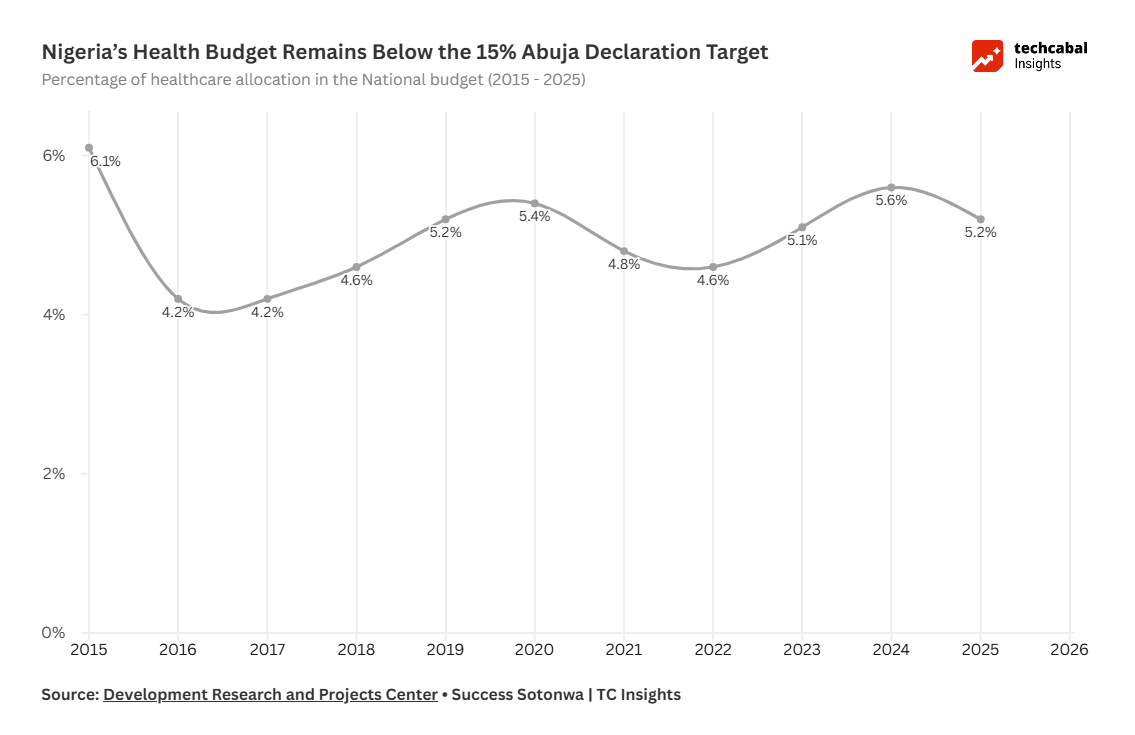

Nigeria’s reliance on informal care reflects chronic underinvestment in primary healthcare. Under the Abuja Declaration, the government pledged to allocate 15% of its national budget to health. In 2024, health received roughly 5%. Recent budget allocations remain far below the target.

PHCs — intended as the backbone of service delivery — remain under-resourced in many states. In that vacuum, informal providers have become default care providers.

Reversing this trend requires more than rhetorical commitments. It requires sustained increases in health financing and, critically, improved execution. In some years, capital releases to the Ministry of Health have fallen far short of appropriated amounts. Closing the gap between budgeted funds and actual disbursement is as important as increasing headline allocations. Beyond financing, several pragmatic reforms could strengthen system coherence:

Legislate clearer integration pathways: Streamline professional oversight and formalize defined roles for accredited alternative and complementary medicine providers.

Institutionalize structured task-shifting: Expand and supervise accredited Tier 2 PPMVs under the existing Task-Shifting and Task-Sharing framework to deliver defined primary services safely.

Adopt referral-based TBA models: Incentivize traditional birth attendants to escort patients to facilities for skilled delivery rather than conduct high-risk home births.

Digitally integrate reporting: Deploy low-cost mobile reporting tools linked to DHIS2 to capture anonymized case data from informal outlets.

Expand micro-insurance access: Design NHIA-backed micro-insurance products that allow accredited community providers to serve as entry points into the formal coverage network.

Informal providers are not anomalies to be eliminated. They are embedded actors in Nigeria’s health ecosystem. Ignoring them perpetuates fragmentation; regulating and integrating them could reduce harm.

Ultimately, strengthening primary healthcare remains the foundation. But until PHCs are consistently funded and functional, informal providers will remain central to access. The task now is to govern and integrate them deliberately.

Also read: Access to credit financing for PPMVs in Nigeria

Explore data-driven insights on Africa’s tech ecosystem in the State of Tech in Africa Report 2025.