Much can be said about how technological innovation drives institutional change. Artificial intelligence is no exception. For all the arguments against its usage, one must at least consider the positive spillover effects it brings. It has contributed to most African nations rethinking how they integrate technology into everyday life. Around two-thirds of African countries have enacted formal data protection laws, and several others are implementing AI strategies.

Yet, there’s no sidestepping the elephant in the room—the argument that building these strategies without having laid the infrastructural groundwork is akin to putting the cart before the horse.

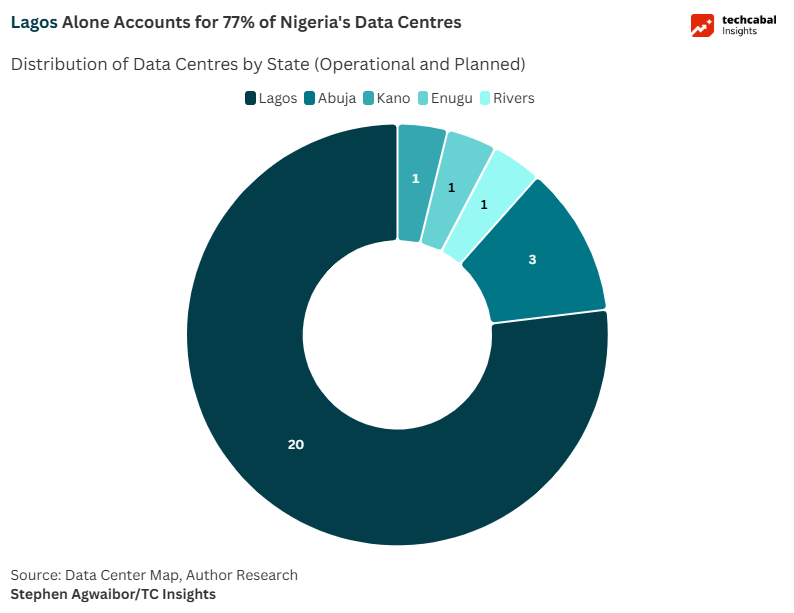

Nigeria, a self-styled beacon of the African digital economy, is making strides. TechCabal Insights’ mapping verified 26 distinct data centre facilities across five states (Lagos, Abuja/FCT, Kano, Enugu, and Rivers). While this list may not be exhaustive, it captures facilities with credible evidence. Of these, 18 are live colocation sites (shared facilities where multiple companies host servers), four are live but limited-use (disaster recovery only, telecommunications-specific, or not independently verified), and four are pipeline projects under construction or formally announced.

Live colocation sites provide about 50 MW of declared IT capacity. Some operators, including NTT Fabac, ipNX VI, and Excelsimo, don’t publish figures, so the total is likely higher. With design specs from operators like OADC Lagos included, capacity could reach about 124 MW. Most of this is concentrated in Lagos, which hosts 77% of facilities. Far from being abnormal, such clustering mirrors how global data centre hubs emerge around infrastructure advantages.

Why Lagos dominates

Lagos’s concentration reflects infrastructure fundamentals that drive data centre development globally. The city hosts multiple submarine cable landing stations, dense fibre interconnection, Internet Exchange Points (IXPs), enterprise demand, and relatively better power contracting options.

This mirrors global hubs like Ashburn in Virginia, Singapore’s Jurong, and London’s Docklands, where cables, power, and connectivity converge. McKinsey also notes that AI-ready workloads cluster in places with large power blocks and deep network backhaul.

As a result, Lagos is the heart of Nigeria’s digital economy. But this overconcentration brings risks. Any outage, flood, or grid failure in Lagos could disrupt services nationwide.

Current operational capacity

Among Nigeria’s 18 live colocation sites, the largest contributors include:

- Africa Data Centres LOS1: Currently at 10MW but with plans to scale to 20.65MW (Eko Atlantic, Tier III)

- Rack Centre LGS2: 12MW (Lagos)

- MTN Sifiso Dabengwa Phase 1: 4.5MW (Ikeja)

- INQ.Digital Nigeria: 4MW (Ikoyi)

- Digital Realty/Medallion LKK2: 2MW (Lekki)

- Rack Centre LGS1: 1.5MW (Lagos)

- Equinix LG1: 8.16MW (Plans to increase capacity to 17MW )

OADC Lagos lists a 24MW design specification, though the current live load is smaller at 1.5MW. Beyond Lagos, the government-run Galaxy Backbone’s Shared Services Centre (0.825MW) and Layer3 provide redundancy in Abuja, while Kano hosts Nigeria’s only Uptime Institute Tier IV-certified national data centre.

Hyperscale expansion ahead

Several Nigerian data centre pipelines are focused on large hyperscale projects built for cloud and AI deployment. However, despite announcements, none are fully operational for AI-related workloads at the moment.

- Nxtra by Airtel: 38MW campus in Lagos, aiming for hyperscale by 2026

- OADC Lagos: 1.5MW live, 24MW planned

- Equinix LG3: Scheduled for 2025 (capacity not disclosed)

- Equinix PR1: Planned in Port Harcourt

- Kasi Cloud: Lekki campus in development

- MTN (Sifiso Dabengwa): 4.5MW operational, with plans to scale to hyperscale

Nigeria’s installed IT load could exceed 150MW by 2027 if all proceeds as planned.

Aerial View of the Rack Centre LGS 2 during construction / Source: Rack-Centre

ALSO READ: Africa’s AI divide: The three tiers of digital readiness

AI and sovereign compute

AI is transforming data centre needs worldwide. McKinsey estimates that by 2030, up to 70% of global demand will be for AI-ready, GPU-dense infrastructure, growing at about 33% annually from 2023.

Africa wants to get a slice of the AI pie. Nvidia’s $700 million partnership with Cassava Technologies to deploy GPU clusters shows growing intent to capture part of the AI market.

For Nigeria, hosting sovereign AI workloads could cement its role as West Africa’s compute hub.

Cloud adoption trajectory

Currently, many Nigerian enterprises host workloads in South African cloud regions, including AWS Cape Town and Azure Johannesburg. As local data centre capacity matures, incentives for cloud providers to establish Nigerian regions increase.

The combination of hyperscale colocation facilities and regulatory requirements could hasten this transition toward local cloud zones.

Regional and global context: Nigeria’s growing position

According to the Africa Digital Infrastructure Report, Africa operates about 200 live commercial data centres delivering 500MW of IT load, supported by 57 IXPs and eight public cloud regions. South Africa dominates with roughly 70% of capacity across 56 data centres, anchored by Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud regions. Nigeria ranks second, representing roughly 15% of Africa’s data centre IT load.

Nigeria, Kenya, Egypt, and Morocco form the Tier-2 group—markets under 150MW capacity today but growing fastest, often exceeding 25% compound annual growth rate. D4D/Xalam estimates Africa needs approximately $6 billion more in data centre investment by 2030 to meet demand.

Placed in a global context, Nigeria’s 26 facilities pale significantly, a rounding error when compared with mature markets like the United States (5,426 facilities). Yet, Nigeria shows a strong pipeline development trajectory within Africa.

Economic impact and trade-offs

More local data centres mean faster internet for Nigerians, stronger fintech and e-commerce performance, reduced spending on offshore hosting, and easier compliance with Nigeria’s Data Protection Act (2023), which limits cross-border data transfers.

However, expansion accompanies significant trade-offs. Diesel reliance raises operational costs and emissions, and overconcentration in Lagos could pose systemic risks.

Planned projects could cost between $620 and $930 million, with each megawatt priced anywhere between $10 million and $12 million locally. Altogether, analysts expect up to $1.6 billion in new data centre investments by 2027.

Infrastructure constraints: Power as the binding factor

Power remains the biggest bottleneck. Nigeria’s grid has never carried more than 6 GW for its 230 million people. By contrast, South Africa manages 48 GW for just 63 million. This massive capacity gap explains why Nigerian data centres cannot depend on the grid and must design for self-sufficiency. Without significant grid improvements, Nigeria risks higher costs that could make its facilities less competitive worldwide.

AI makes the challenge even harder. GPU-heavy racks demand steady electricity and advanced cooling. Unlike standard CPU racks that used 5–15 kW, today’s AI racks need 20–40 kW each, plus liquid cooling and large, continuous power blocks. Nvidia projects that its Kyber System servers could draw up to 600 kW per rack by 2027, up to 20 times current usage. A counterargument may be made that Africa does not require as much computing power as is used in the US, EU or China.

Nonetheless, one point stands cogent. Rapid AI adoption implies massive energy demands. The result is soaring costs, heavier carbon footprints, and requirements for hyperscale campuses that consume hundreds of megawatts—investment levels rarely seen in Nigeria or indeed Africa’s infrastructure sector.

MTN’s CEO Karl Toriola has even suggested that nuclear power—especially small modular reactors—may be key for Africa’s AI future. However, only one such plant exists on the continent—in South Africa. Egypt plans to have an operational plant by 2028.

Market outlook

If all planned projects are delivered, Nigeria’s capacity could pass 150MW by 2027, solidifying it as second only to South Africa. For now, most hyperscale facilities remain in development, so the most extreme energy demands have not yet arrived. But planning for them cannot wait.

With less than 6GW on its national grid, Nigeria must confront its power deficit now. Without reliable, large-scale electricity, growth in facilities alone will not secure competitiveness. Sustaining the momentum will rest largely on how Nigeria is able to solve the energy conundrum.

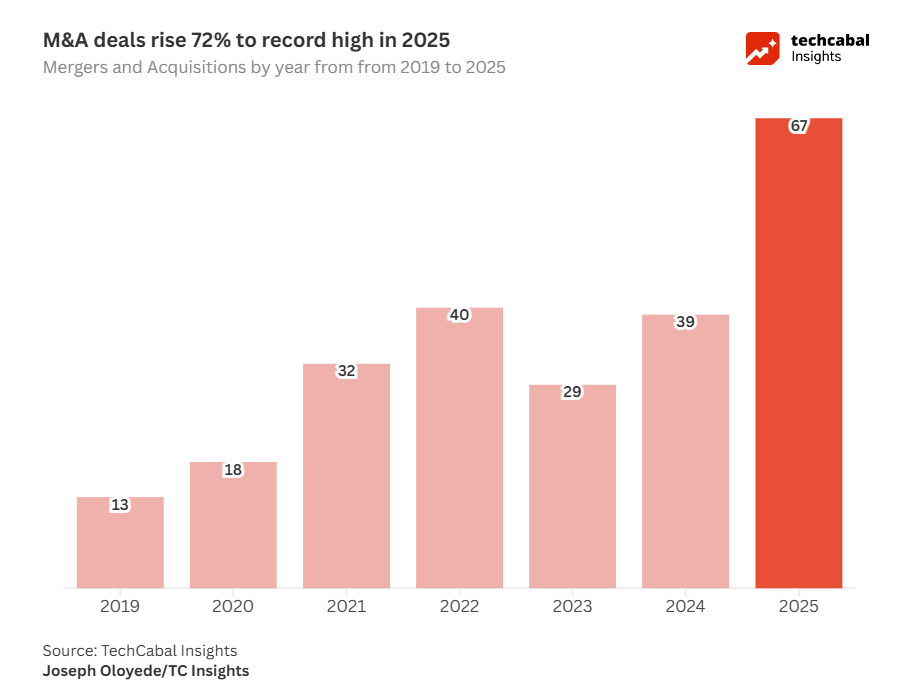

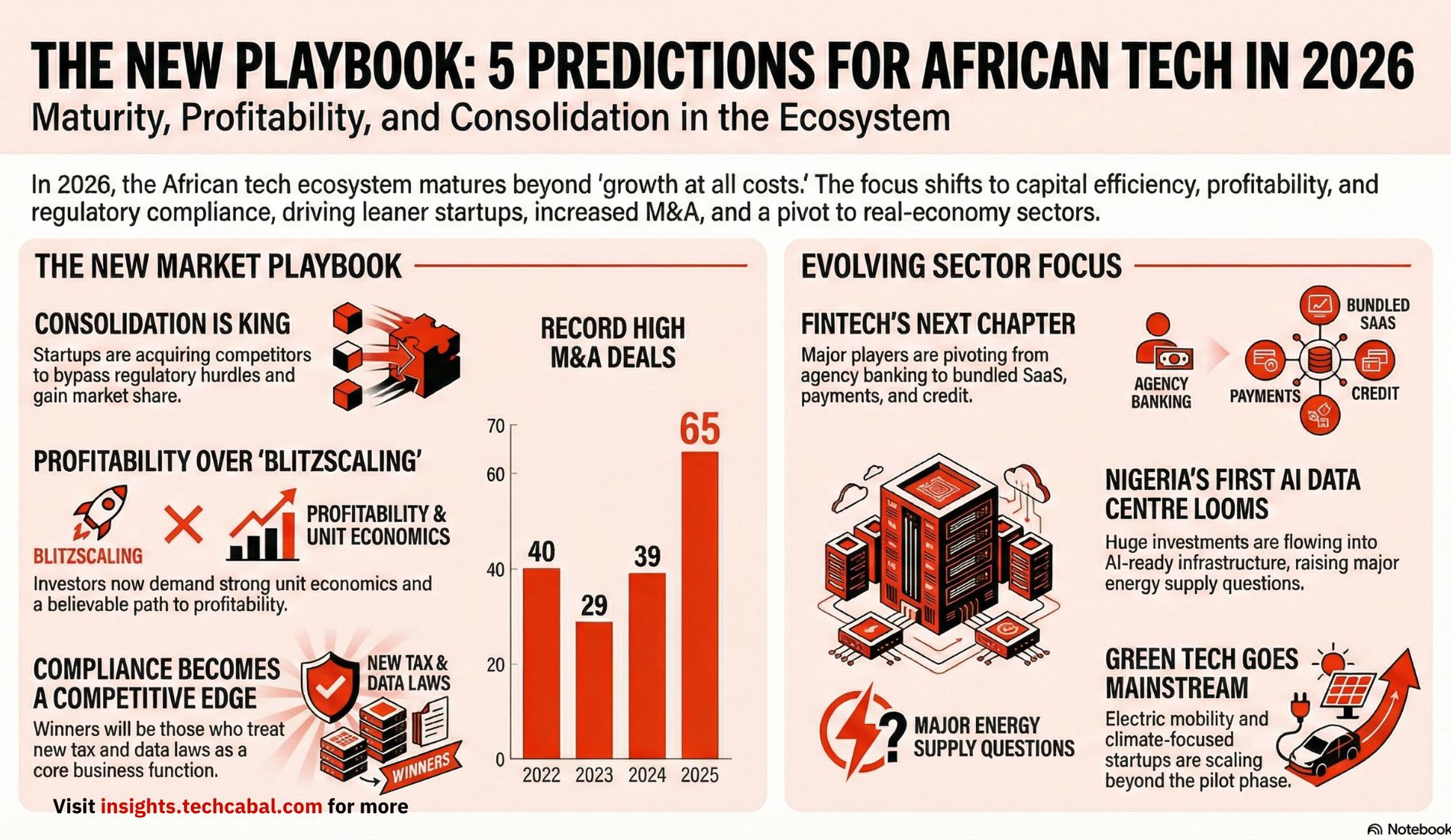

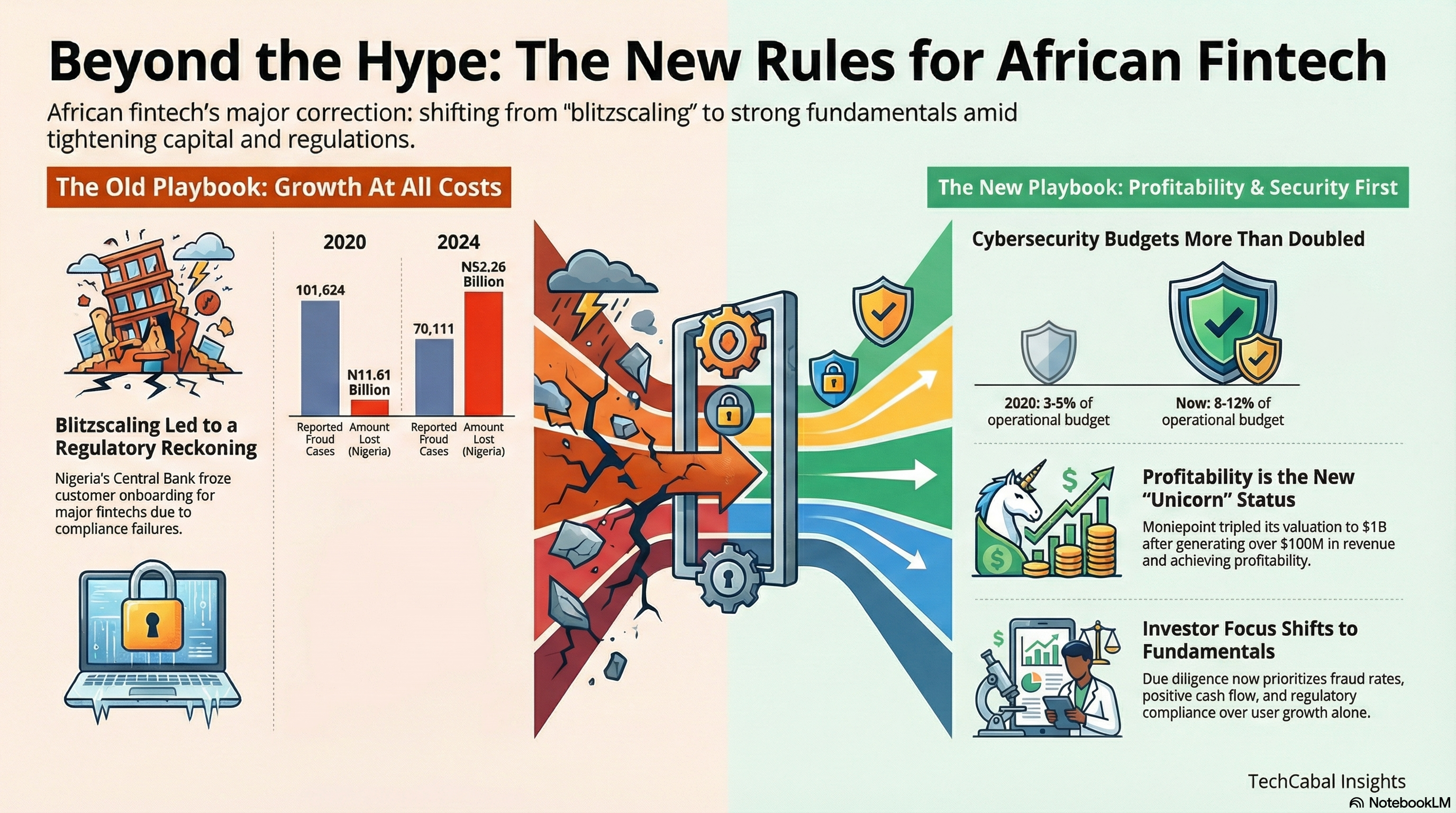

The State of Tech in Africa Report H1 2025 gives a robust assessment of what is happening in African tech and projections for the future. Download it here.