By Prince Enyiorji

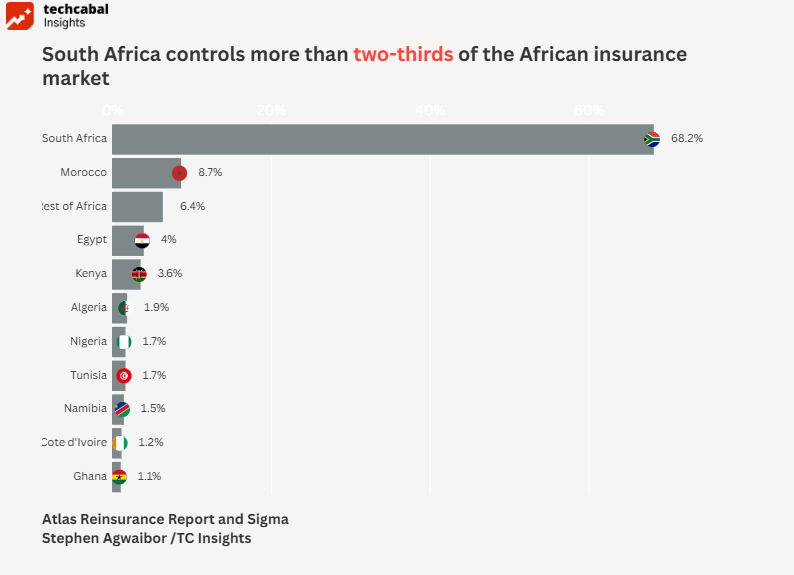

The African insurance sector provides an interesting case for consideration. By one account, the market is valued at $92.9 billion. However, the evidence suggests that this has a minimal impact on the lives of ordinary Africans. While developed markets boast insurance penetration rates of 8–11%, most African countries languish below 3%. Nigeria and Ethiopia sit at 0.3%. Kenya, East Africa’s most developed insurance market, reaches just 2.25%. Only South Africa, an outlier, achieves an 11.54% rate.

In 2024, the global AI for insurance market was valued at $8.13 billion and is projected to reach $141.44 billion globally by 2034, driven by a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of approximately 33%. This technology represents a powerful catalyst—serving as a bridge between the continent’s current position and its aspirational future.

Reimagining accessibility

To start with the obvious, Africa has an insurance problem. Analysts and insurers often cite the same reasons for low penetration: people don’t trust insurers, premiums are too expensive, awareness remains low, and distribution networks fail to reach customers. AI addresses these problems from an entirely different angle by reimagining how insurance works in African contexts, rather than selling more of the same products through the same channels.

AI-driven platforms reduce operational costs significantly. When insurers eliminate layers of manual processing, they can offer products at prices that fit local markets. More importantly, AI helps them tailor, price, and distribute micro-insurance products through mobile platforms — the one infrastructure that has truly reached African markets.

Consider BIMA’s approach in Tanzania, Ghana, and Kenya. By leveraging mobile technology to offer affordable health, life, and personal accident insurance, they’ve covered over 30 million customers—people who would never have walked into a traditional insurance office. Their model works because AI handles the heavy lifting of risk assessment, pricing, and claims processing at scale, potentially allowing them to serve low-income customers profitably.

The real test in claims automation

Penetration is only half the battle. The other half is trust, and nothing destroys trust faster than poor claims experiences. Policies sold with fanfare, then claims that take months to process, require endless documentation, and often end in disputes.

This is where African insurers are showing some promise. In April 2024, M-TIBA, Kenya’s health insurance platform, integrated AI into its claims processing system, reducing claim approval times from the regulatory maximum of 90 days to just hours. Over 40% of claims can now be automated, with the AI swiftly approving straightforward submissions while claims assessors focus on underwriting the more complex cases. In the course of three months, this technology automatically assessed claims for leading health insurers, facilitating faster payments to providers.

Jubilee Insurance, also in Kenya, introduced machine learning tools to adjudicate medical claims. Similar implementations in Europe have shown 70% automation rates in document processing, suggesting African insurers are on the right track.

The strategic implications are clear. Fast, transparent claims processing builds the trust African insurance markets desperately need. When a farmer in rural Kenya can file a crop insurance claim via mobile phone and receive payment within days instead of months, word spreads.

Telematics-based auto insurance, where AI analyses driving behaviour from connected devices, offers personalised policies based on actual driving habits rather than relying solely on demographic data. In African cities with chaotic traffic and limited accident data, this approach makes risk assessment more accurate while rewarding safe drivers with lower premiums.

ALSO READ: Can technology transform Africa’s food security crisis?

The sobering reality

The case studies lend weight to the premise that AI can close the insurance gap. Still, there are formidable obstacles that remain outstanding.

In Kenya, up to 50% of insurance data becomes inaccurate by the time it’s analysed, trapped in paper-based systems or fragmented across disconnected platforms. Reporting timelines stretch from weeks to months. East Africa’s 1.39% insurance penetration means insurers have limited historical data for training AI models. If your training data comes from other markets, your AI might make catastrophically wrong assumptions about African risk profiles.

Although modern AI systems can work with unstructured data, the risk of hallucination and algorithmic bias looms large when models optimise for fluency over accuracy. An AI trained to assess health insurance claims using European medical cost data might drastically misprice risk in Lagos or Nairobi, where healthcare economics differ fundamentally. Training models on local data requires substantial computational resources. According to the Africa Data Centres Association’s 2025 survey, only 36% of African operators have deployed AI-ready infrastructure. Power reliability ranks as the second-biggest constraint. For insurers, this means either building costly on-premise systems or relying on foreign cloud providers, which raises concerns about data sovereignty and latency.

There’s an undeniable skills gap. The Africa InsureTech Forum 2024 highlighted this repeatedly: insurers want to adopt AI but struggle to find actuaries, data scientists, and engineers who understand both insurance and machine learning. The few qualified professionals command premium salaries or leave for opportunities abroad. Dependence on expensive foreign consultants undermines the cost advantages AI promises, just as building in-house capabilities may take years.

Regulatory frameworks lag behind innovation. For example, the UK launched a “Supercharged Sandbox” in June 2025, partnering with NVIDIA to help financial services firms experiment with AI under regulatory supervision. Singapore mandated AI governance requirements for financial institutions in December 2024. African regulators, however, move more slowly, a byproduct of the low-trust environment in which they are situated. Kenya announced plans for an insurance regulatory sandbox in 2019; implementation remains incomplete. Questions about algorithmic bias, data privacy, and consumer protection are legitimate, but the absence of clear frameworks leaves insurers navigating uncertainty. When an AI system denies a claim, who is accountable? How should insurers explain automated underwriting decisions? African regulators have yet to provide answers.

The way forward: What needs to happen?

So, where does this leave us? AI could genuinely transform African insurance, but success requires clear-eyed pragmatism rather than technological optimism. Developers and insurers must design AI solutions that fit African contexts instead of importing them wholesale from developed markets. This means designing for low bandwidth, intermittent connectivity, multilingual interfaces, and varying levels of digital literacy. The technology needs to be robust and forgiving, and not fragile and demanding.

Data strategies must be creative. With limited historical data, insurers should explore alternative sources, such as mobile money transaction patterns, satellite imagery for agricultural insurance, and social network data. This must be done ethically, with explicit consent and robust privacy protections in place. The last thing African insurance needs is an AI-driven data exploitation scandal.

Partnerships are also essential for traditional insurers. They would need to collaborate with insurtech startups, mobile network operators, and technology companies. Insurtechs like Turaco and mTek are developing innovative solutions precisely because they’re not burdened by legacy systems. Rather than viewing them as threats, established insurers should see them as laboratories for experimentation.

Meanwhile, regulators need support to develop frameworks that protect consumers while enabling innovation. This requires engagement from technology companies, consumer advocacy groups, and international development organisations; certainly not a job for insurers alone. Getting this right is crucial because regulatory missteps could set the sector back years.

To measure success, penetration should be prioritised over efficiency because an AI system that makes insurance companies more profitable, while coverage remains below 3%, is not a true success. The goal should be to provide products that reach 96.4% of Nigerian businesses currently operating without insurance—from smallholder farmers to informal sector workers and the millions who need insurance but can’t access or afford it.

A qualified optimism

The technology is powerful, the market need is enormous, and the business case is compelling. But execution remains king. AI isn’t a silver bullet. It won’t magically solve trust deficits built over decades, overcome infrastructure limitations, or eliminate poverty. What it can do, if implemented thoughtfully, is make insurance more accessible, affordable, and responsive to the needs of Africans.

What is now required is the courage to experiment, the humility to learn from failures, and a commitment to outcomes that matter: serving the hundreds of millions of Africans who deserve the security that insurance can provide.

Prince Enyiorji is a product manager specialising in AI-driven automation across financial services, agriculture, and nonprofit sectors. He holds a graduate degree in Business Analytics and AI from American University, Washington DC.

The State of Tech in Africa Report H1 2025 provides a comprehensive assessment of the current state of African tech and offers projections for the future. Download it here.