Can Nigerians afford a pot of soup?

For a Nigerian earning the minimum wage of ₦70,000, cooking just one pot of chicken stew a week would consume nearly an entire month’s salary. The 2024 PricePally Stew Index, which tracks the cost of a fixed basket of stew ingredients—tomatoes, peppers, onions, oil, and chicken—across multiple markets in Lagos, including Ajah, Mile 12, Mushin, and Oyingbo, highlights how steep food inflation has become. According to the index, a pot of chicken stew cost ₦7,085 in 2023, but by 2024, the price had jumped to ₦15,034—a rise of about 112%. That single pot alone takes up 21.5% of a minimum-wage earner’s salary.

Most Nigerians don’t earn enough to cope with this new reality. The PiggyVest Savings Report 2024, which surveyed over 10,000 Nigerians across various income levels and occupations, provides a snapshot of how households are adapting. It found that more than one in three Nigerians live on less than ₦100,000 a month. For these households, food takes the largest share of spending, with 83% identifying food and groceries as their biggest expense, far ahead of transport (48%) and utilities (38%). At the same time, food is the category most affected by inflation. Seventy-six per cent of respondents say food prices have risen the most in the past year. It is no surprise then that 43% of respondents say they do not save at all.

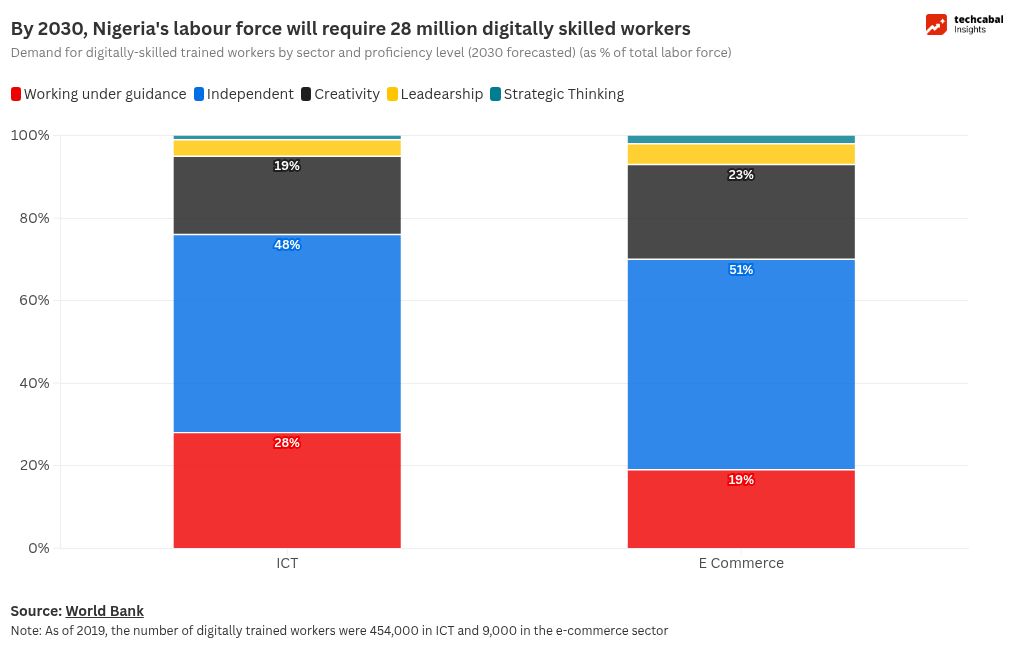

Unemployment and underemployment make it harder for young Nigerians to cope with rising costs. According to the NBS, the youth unemployment rate stood at 6.5% in 2024; however, this figure is based on a redefinition of employment introduced in 2023. In 2020, the rate was 53.4% for 15–24-year-olds and 37.2% for 25–34-year-olds, figures that many argue better reflect the reality young people face today. A 2024 Afrobarometer survey also found that rising cost of living, unemployment, and food shortages rank among the most pressing concerns for Nigerians.

ALSO READ: How African farmers are using AI to reimagine what’s possible

How is technology solving this problem?

Nigerian startups are positioning themselves as buffers against food inflation. A notable example is PricePally, which has established a food cooperative that enables households to pool their demand and split bulk orders. By cutting out the middleman and offering wholesale pricing, PricePally claims to reduce costs by up to 25% for families while boosting farmers’ income by over 30%. In 2021, it . The startup raised $1.3 million in seed funding in 2023 to expand its model across Nigerian cities.

Another startup, Vendease, takes a B2B approach, targeting restaurants and food businesses. According to the startup, it moved more than 400,000 metric tonnes of food for 2,000 clients, saving them $2 million in procurement costs and $500,000 in wastage over a 12-month period.

A new entrant, Grup Limited, is exploring a group-buying model that pools neighbourhood demand and sources directly from farmers. It claims this can make food up to 40% cheaper than open market prices.

Beyond these consumer platforms, agritech startups are also working on the supply side, helping farmers improve yields and reduce waste. Platforms like Babban Gona, ThriveAgric, and ColdHubs provide finance, storage, and other essential inputs that, in the long run, can ease pressure on food prices.

ThriveAgric has supported more than 800,000 smallholder farmers across Nigeria, providing them with finance, inputs, and market access. By 2022, the company reported producing over 1.5 million metric tonnes of grains and investing more than $100 million in agricultural financing, accounting for about 5% of Nigeria’s maize output.

According to ColdHubs’ 2024 impact report, the company operates 58 solar-powered cold rooms across Nigeria, serving more than 11,100 farmers, retailers, and traders. Its cooling and logistics network has saved over 13.8 million kilograms of food from perishing and helped users increase their incomes by an average of 63.5%.

ALSO READ: Can technology transform Africa’s food security crisis?

Solving food problems is not easy

Running a food-tech company in Nigeria comes with heavy baggage. For Vendease, operating the logistics side of food purchasing was expensive. Trucks, warehouses, and fuel price hikes added up quickly.

The company’s model of managing procurement, logistics, and extending credit to businesses looked promising in theory, but proved difficult to sustain. Inflation and naira devaluation squeezed margins, and by late 2024, reports surfaced of unpaid vendors and debt obligations of over ₦1.5 billion.

Vendease has since pivoted to a software-driven approach, focusing on streamlining procurement, sales, and payments while leaning less on costly warehouses and trucks.

These struggles don’t make the idea behind Vendease irrelevant. Instead, they highlight the risks of a capital-intensive model in fragile economies like Nigeria’s, where companies face greater exposure to macroeconomic shocks.

The experience of these tech companies shows that technology alone cannot neutralise Nigeria’s food inflation. For digital tools to produce meaningful results, structural enablers must fall into place. This includes introducing policies that reduce logistics bottlenecks, improving electricity access in rural areas, and strengthening market linkages.

These reforms would help startups scale sustainably, rather than merely surviving policy shocks. As long as inflation and weak infrastructure persist, technology will remain a partial buffer rather than a complete solution.