AI usage has broken new ground, setting never-before-seen records in consumer tech globally. In October 2025, Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, announced that ChatGPT had surpassed 800 million weekly active users (WAU). The surge is all the more remarkable given that ChatGPT only launched in November 2022 and is on track to reach one billion WAUs by year’s end at an adoption rate surpassing electricity or even the internet. Today, 1.2 billion people reportedly use AI.

While this is good news for techno optimists, a more helpful way of tracking AI adoption is by measuring its diffusion. Microsoft recently released its AI Diffusion Report, which provides three complementary indices to assess AI progress: The AI Frontier Index, which tells us where the world’s leading AI models are being made, the Infrastructure Index, which measures how well countries build and scale AI, and the Diffusion Index, which measures how AI is being adopted—from individuals to governments.

To narrow the focus, we’ll consider how the report places Africa within the broader AI race and what the data reveals about the continent’s readiness. To begin, let’s address the question of what diffusion is.

What is technological diffusion?

Technological diffusion is the process by which innovations—whether new products, processes, or management methods—spread within and across economies. Technology diffusion is a crucial driver of productivity growth, and empirical evidence supports this assertion. A noteworthy example is South Korea, whose government in the 1960s prioritised research and development, infrastructure investment, and incentives to promote technological adoption, galloping from a nominal GDP per capita of $158 in 1960 to more than $35,000 today.

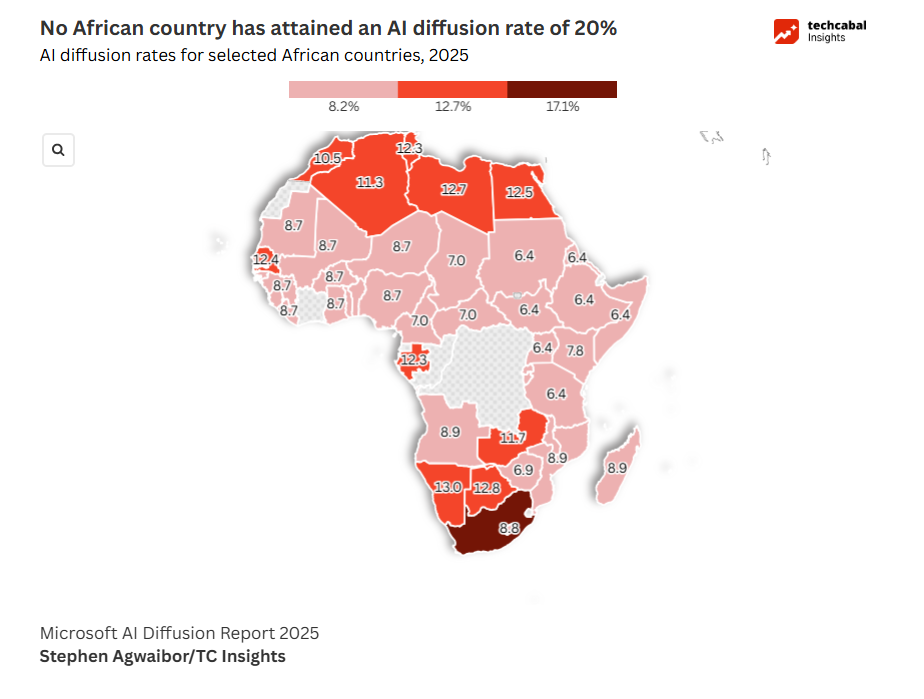

AI diffusion, therefore, refers to the extent to which AI is adopted and utilised across various populations. According to the report, Microsoft captured the rate of AI diffusion by analysing aggregated and anonymised telemetry from over one billion Windows devices, allowing it to estimate the prevalence of AI-related activities across regions. Microsoft’s data shows no African country has yet achieved a 20% AI diffusion rate. For context, the top three countries with the highest overall diffusion rates are the UAE (59.4%), Singapore (58.6%), and Norway (45.3%).

Although the rise of AI promises significant economic opportunities, it also presents substantial challenges. Digital technologies, including AI, tend to create natural monopolies by concentrating power and profits among a small set of companies hosted in a few dominant countries. Because wealthier nations possess incentives, skills, and institutions to adopt AI effectively, a disequilibrium arises that fuels brain drain from resource-constrained countries to economic powerhouses, widening the gap between the haves and have-nots.

The building blocks of AI

We can better understand AI diffusion by examining the building blocks of AI: the elements that countries need to have in place to reap the manifold benefits the technology offers. These include:

- Electricity

- Data centers

- The Internet

- Digital and AI skills

- Language

Electricity

Currently, Africa remains at a deficit in each of these five building blocks. Take electricity, for example. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that electricity consumption from data centres amounted to around 415 terawatt-hours (TWh) in 2024 and has been growing at a rate of 12% over the past five years. By 2030, this could increase to more than double, reaching 945 TWh. To put this into perspective, the entire African continent generated 919.22 TWh of power in 2023.

The report notes that 18 of the 20 countries with the most significant electricity deficits are in Sub-Saharan Africa. This region now accounts for 85% of the global population without access to electricity.

Promisingly, a few projects on the continent aim to address this challenge. One of them is the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, a 5.15 GW hydroelectric plant that is among the largest in the world in terms of capacity. More such projects need to come to life to bridge the stark electricity gap.

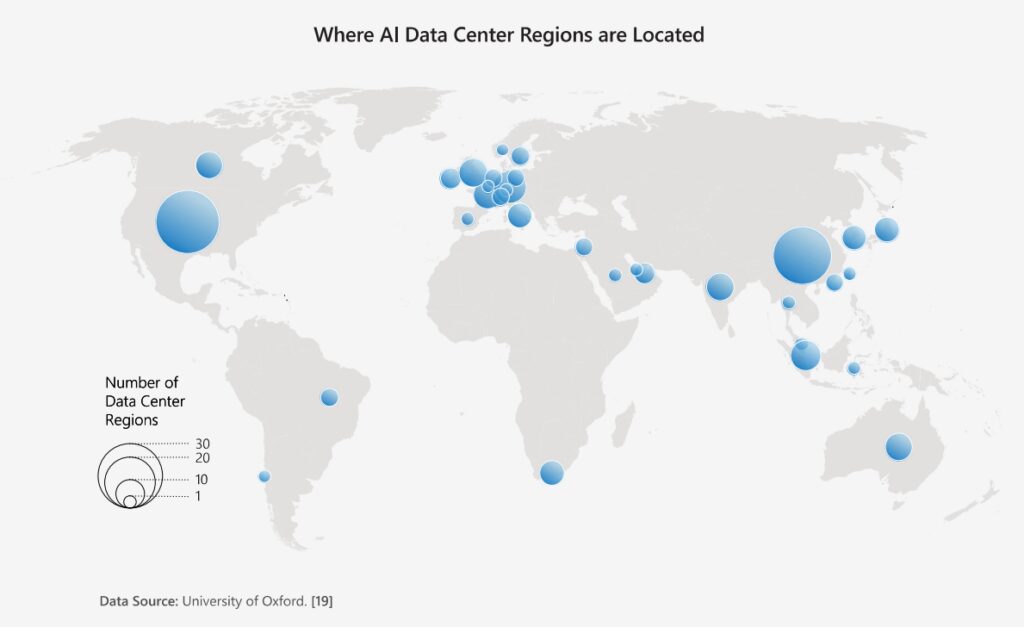

Data centers

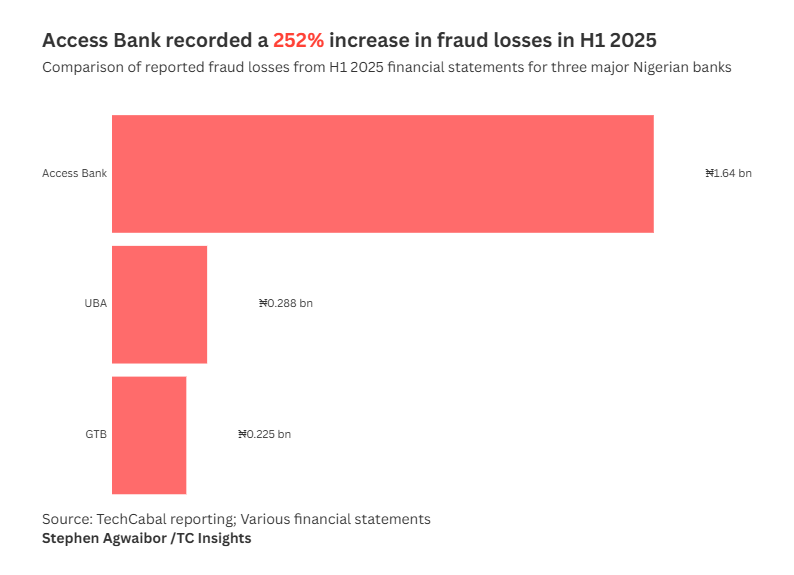

In an earlier post, we addressed whether Africa’s data centres can power its AI future. Using Nigeria as a case study, we highlighted the current state of play of its data centres. Outside of South Africa, Nigeria holds the largest functional data centre in Lagos with a capacity of 12MW. However, these facilities are not yet at a hyperscale level; that is, they are primarily designed for cloud services and have not been retrofitted or expanded for AI deployment. The capital-intensive requirements of data centres, along with the immense GPU and power consumption they demand, make undertaking such projects a daunting task. The report notes that only one functional hyperscale facility currently exists on the continent, in South Africa. Nevertheless, there are indications that this may change in the not-too-distant future.

ALSO READ: Can Nigeria’s data centres power Africa’s AI future?

The Internet

Globally, internet penetration has been on an upward trajectory. In 1997, only 2% of the world’s population was online. Today, the global average is around 67%. Still, the picture is more nuanced when the numbers are disaggregated. Internet use is rising in middle-income countries, while low-income countries are falling further behind. The World Bank says these countries need to expand and upgrade their broadband infrastructure to handle the explosive growth in data and enable broader digitalisation. According to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), an outlay of $400 billion is needed to connect the unconnected between 2020 and 2030.

In Africa, internet penetration ranges from 92.2% in Morocco to just 12.5% in Burundi. Only 37% of people in Sub-Saharan Africa are online, limiting access to life-improving opportunities. The impact of connectivity is significant: 3G coverage has been linked to a 10% reduction in extreme poverty in Senegal and a 4.3% reduction in Nigeria. Data-driven analytics also help small and medium enterprises boost sales and competitiveness. If AI is to scale across the continent, universal internet access must be prioritised.

Digital and AI skills

In a report released earlier this year, we advocated for strengthening digital and AI literacy to facilitate more comprehensive participation in an AI-driven economy. With a median age of 19, Africa’s workforce will increasingly need these capabilities across millions of emerging roles.

As a white paper on AI and Africa’s future of work emphasises, developing homegrown talent in AI research, innovation, design, policy, and governance is critical. This involves developing expertise in the technical foundations of AI, including computer science, machine learning, natural language processing, and engineering.

Language

One particularly striking AI deficit is in languages. Around half of internet content is in English—a language spoken natively by just 5% of the world’s population—meaning AI training datasets are heavily skewed toward it.

The report notes that in Malawi, less than four per cent of people speak English, while prevalent languages like Chichewa, Chitumbuka, and Chiyao are virtually absent from LLMs. Even widely spoken African languages suffer from underrepresentation. Swahili, with over 200 million speakers (comparable to the number of German speakers), has 500 times less digital content online. Yoruba, spoken by over 50 million people, achieves only 55% accuracy in translations using leading LLMs.

Progress is emerging, however. Researchers funded by the Gates Foundation recently launched African Next Voices, the largest AI-ready dataset for African languages, featuring 9,000 hours of recorded speech across 18 languages. African startups, such as Lelapa AI and Masakhane, are also developing natural language processing solutions to advance digital inclusion and create AI that reflects the continent’s linguistic diversity.

Africa’s path forward

Rather than dwelling on the scale of the energy and infrastructure gaps, it may be more useful to recognise that Africa’s AI journey doesn’t need to replicate the exact trajectory of more prosperous Western nations. The continent has navigated challenges in its own unique way in the past—from mobile money transforming banking without extensive ATM infrastructure, to mobile internet reaching rural areas without landlines.

The key is understanding how the building blocks create multiplier effects. Solving electricity unlocks data centres. Data centres enable internet expansion. Internet access makes skills training viable. And skills training allows Africans to build AI that speaks their languages and addresses their needs. Catching up and transitioning from consumer to innovator will require building brick by brick to strengthen the continent’s position in tomorrow’s AI economy.

Explore how Africa’s digital infrastructure is reshaping commerce. Download the Future of Commerce 2025 report.